Our liver plays a role in regulating our central biological clock, scientists from CNRS and Université Paris have discovered. The results of their study, published on 17 May in Science Advances, show that the biological clock of mice can be reprogrammed by inserting human liver cells into the animal’s liver.

Organisms rely on a biological clock known as the ‘circadian’ clock to regulate their activity according to the time of day. A central clock, constituted by a group of brain cells — the suprachiasmatic nuclei, or SCN — synchronises the circadian clocks present in all body’s organs, called ‘peripheral’ clocks. Until now, synchronisation of the circadian cycle in mammals was thought to be a one-way mechanism in which the suprachiasmatic nuclei alone synchronized the peripheral clocks.

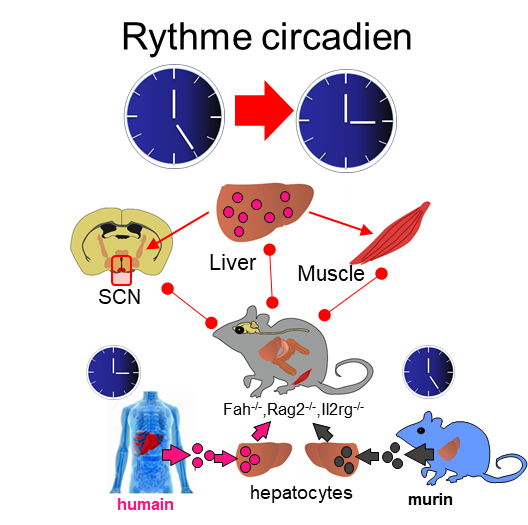

Scientists from CNRS, Université Paris Cité1 and the University of Queensland2 , however, in the framework of a joint EU endeavour3 , have just shown that the liver also influences peripheral clocks. Teams studied a chimeric mouse model with a liver containing human hepatocytes and observed that the daily cycle of these usually nocturnal animals had advanced by two hours.

The mice became active and began feeding two hours before nightfall, thus becoming partly diurnal. The researchers believe this shift comes from the mice’s central clock being taken over by the human liver cells in this chimeric animal model. These cells can thus affect the entire rhythmic physiology of the animals, including the clocks of the peripheral organs.

Findings suggest that a change in liver clock — for example in pathological condition such as cirrhosis — could affect the synchronisation function of the central clock. This in turn could affect the entire circadian physiology, including the sleep/wake cycle, and contribute to the development of metabolic disease. It also suggests that restoring disrupted liver biological rythm could benefit the entire body metabolism. The hormonal and nervous mechanisms driving this dialogue between the brain, liver and biological clock remain to be identified.

A “humanised” mouse model receives liver cells from healthy mice (control group) or human liver cells (humanised mice). The presence of human liver cells leads to a modification in the circadian clock of the liver and muscle and affects the central clock (the suprachiasmatic nuclei). This results in a phase advance in circadian rhythm in the humanised animal, the metabolism and behaviour of which shifts forward by a few hours.

© Luquet et al./ Science Advances

Notes

- At the Unité biologie fonctionnelle et adaptative (CNRS/INSERM/Université Paris Cité)

- Institute for Molecular Bioscience, The University of Queensland, Australia

- Study carried out as part of the EU-funded HUMAN consortium on Health and the Understanding of Metabolism, Aging and Nutrition.

Mice with humanized livers reveal the role of hepatocyte clocks in rhythmic behavior.

DOI : 10.1126/sciadv.adf2982

Read more

No relationship between Université Paris Cité and the private company operating under the name City University of Paris

Université Paris Cité discovered that a private higher education establishment initially called Intelligest has recently changed its company name for ‘City University of Paris’. Université Paris Cité points out that it has no links whatsoever (association,...

read more

Results of the 2025 Call for Projects with the University of Toronto

The 2025 call for projects between Université Paris Cité and the University of Toronto met with great enthusiasm within the scientific communities of both institutions. Eighteen proposals were submitted by pairs of researchers; five projects were selected at the end...

read more

Call for projects 2025 UPCité – King’s College London

The call for projects between Université Paris Cité (UPCité) and our privileged partner King's College London (KCL), has been launched this friday, May 9th 2025. The objectives Université Paris Cité and King's College London are offering offering a seed funding for...

read more

UM6P and UPCité Offer Two Joint PhD Scholarships

Mohammed VI Polytechnic University (UM6P) and Université Paris Cité (UPCité) are strengthening their collaboration by offering two joint PhD scholarships for thesis projects affiliated with one of UPCité’s Graduate Schools. This call aims to reinforce...

read more